As a fire investigator with Hawkins who has previously worked on developing Additive Manufacturing (AM) technologies in research and in the medical device industry, I am particularly interested in dust explosions linked to AM. In this article, I will explore the risk of dust explosions in the AM environment and the current best practices for preventing them.

What Are Dust Explosions?

So, what is a dust explosion? Mr Rolf K Eckhoff states in his book “Dust Explosions in the Process Industries” that “any solid material that can burn in air will do so with a violence and speed that increases with increasing degree of sub-division of the material.” ¹ As we all intrinsically know, if we are trying to start a fire in an open hearth or stove, we make kindling first, breaking a large piece of wood into smaller pieces rather than attempting to ignite a large log. By making kindling, we increase the surface area of the wood, increasing the degree of sub-division of the wood, enhancing the speed of combustion and reducing the energy requirement for ignition.

A dust explosion can be defined as the rapid combustion of fine particles suspended in the air, often in an enclosed location. This type of explosion can occur when a dust cloud (an assembly of dust particles suspended in air) of the right concentration is exposed to an ignition source, such as a spark or flame. The “right” concentration here refers to somewhere between the upper and lower limit of the ratio between dust and air within the cloud that will support combustion, more on this later.

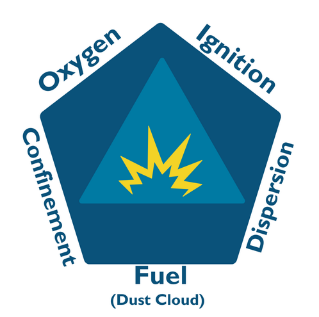

In conventional fire investigation, we use the basic principle of the fire triangle, a simple model for understanding the necessary ingredients for all fires. It consists of three elements: heat (ignition source), fuel, and oxygen. For a fire to ignite and sustain itself, all three components must be present. For dust explosions, this triangle is extended to a pentagon to include the dispersion of dust particles (a dust cloud) and confinement. For a dust explosion to occur, all five elements of this pentagon need to be present. Thus, similarly to our fire triangle, removing any one of these elements can prevent a dust explosion.

The term “ATEX” comes from the French “ATmosphères EXplosibles.” An ATEX environment refers to a workplace where there is a risk of explosive atmospheres due to the presence of flammable gases, vapours, or combustible dust mixed with air. For some AM technologies, particularly those using powder as a raw material, the manufacturing floor is considered an ATEX environment.

What then is a combustible dust? Let’s take a small step back. Dust explosions in general arise from a rapid release of heat produced during the chemical reaction of combustion:

fuel + oxygen = oxides + heat

This means that only combustible materials, ones that are not already stable oxides, can form dust clouds capable of explosion. As a result, clouds of cement or fine sand will not give rise to a dust explosion. If this wasn’t the case, sand storms would be a lot scarier. On the other hand, materials that can give rise to dust explosions include natural organic materials such as grain or sugar, synthetic organic material such as plastics, and even metals such as aluminium, magnesium or titanium. When in a fine particle form, these materials are referred to as combustible dust.

Examples of Dust Explosions

There are myriad examples of dust explosions throughout history involving diverse types of combustible dust and different ignition sources. One example involving the production of metallic powder was at an atomised aluminium powder production plant in Anglesey in 1983. Mr Rolf K Eckhoff’s book “Dust Explosions in the Process Industries” describes the explosion as having swept through the entire plant. Neither the ignition source nor the point of ignition was determined. However, the extensive damage highlights the risk of dust explosions and the progression of the explosion from its point of ignition to the rest of the plant highlights the importance of managing intentional or unintentional dust accumulations in the manufacturing environment.

A more recent incident involving metallic powder happened at a Woburn Massachusetts AM company on the 5th November 2013. A news release from the U.S. Department of Labour stated that the company failed to protect its workforce from the hazards of combustible metal powders like titanium and aluminium alloys.

Key issues included;

- Failing to eliminate ignition sources

- Not alerting the fire department to the additional risk

- Using inappropriate equipment (not ATEX rated equipment)

- Placing workstations near explosion-prone areas

Additive Manufacturing

The case study allows me a convenient time to introduce AM. So, what is it?

Since its inception in 1981 by Dr Kodama of the Nagoya Municipal Industrial Research Institute, many terms have been used to describe the process of creating a three-dimensional object directly from a numerical model by stacking two-dimensional layers. The most prevalent terms, in chronological order, are rapid prototyping, 3D printing, and additive manufacturing (AM). Observing these terms in sequence provides insight into the technology’s development over the past four decades, evolving from a prototyping tool to a fully-fledged manufacturing process.

AM has been at the forefront of innovation in various industries. It has revolutionised the aerospace sector by enabling the creation of components with intricate and organic shapes that were previously difficult or impossible to produce using traditional methods. This technology allows engineers to design components by placing material only where stress acts, thus allowing for more efficient use of material and making parts lighter, which is crucial for improving fuel efficiency and reducing emissions in air travel.

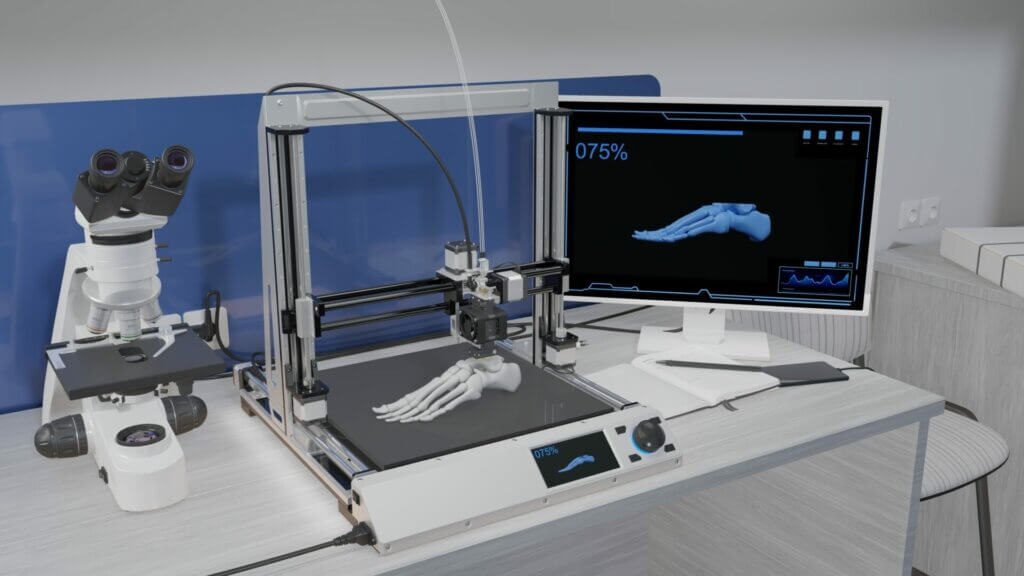

In the medical device industry, AM has facilitated advances in patient-specific implants, prosthetics, and surgical guides, where the device matches the patient’s specific anatomy. AM has also been used to create unique geometries that enhance the clinical benefits of devices, such as orthopaedic implants composed of fine lattices that promote osteointegration.

AM has undergone significant development since its initial use for prototyping. It has evolved into a multi-material, multi-scale manufacturing technology with numerous subsets.

These subsets, although all categorised as AM, differ in the mechanisms by which they create the two-dimensional layers, this can be done in the following ways;

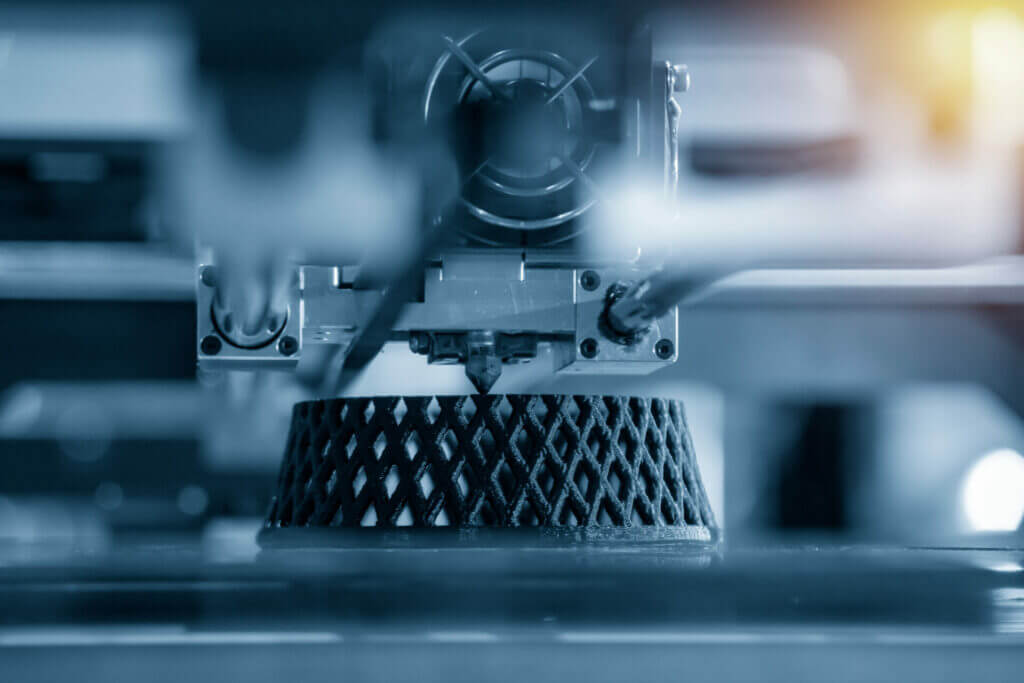

- Extrude molten thermoplastic from a heated nozzle

- Use light, in the form of lasers or projections, to solidify liquid polymer resins

- Deposit adhesives onto metal, polymer, or ceramic powders, creating a green body that must be sintered

- Melting powders by direct exposure to a laser, which, when resolidified, creates a solid mass of material

The raw material input for AM processes varies and can generally be categorised as filaments, resins, or powders. This article will focus on powders, with a particular interest in managing these powders to ensure safe use.

Risk and Prevention

Now that we understand the basics, let us consider the risks of working in an ATEX environment on an AM manufacturing floor that utilises metallic powder as its raw material. The raw material, the powder, is loaded into the 3D printing system, either manually or automatically. This powder is often recycled from previous printing processes so may have already gone through a sieving process, or other pre-printing processes to ensure its suitability for use. Printing occurs and the parts are removed from the powder cake i.e. the mass of powder held within the printer that contains the printed parts. Part removal is often manual and involves extraction of unused powder. After printing, parts go onto secondary processes where they are further refined and unused powder is recycled further. I paint this simple picture of a common AM process to illustrate how much powder is handled during the printing process in an attempt to describe how difficult it is to contain this powder. Powder inevitably escapes the confinement of the various processes and enters the manufacturing environment where it builds up on surfaces and is extracted through air handling systems.

Let me pause this quickly and introduce the concept of primary and secondary explosions. Dust explosions cannot occur unless the dust concentration within a cloud is within certain limits. Too much dust in a cloud and combustion will not occur due to lack of oxygen, too little dust in a cloud and combustion won’t occur due to lack of fuel. If we imagine disturbing a small pile of dust, this will rise and start to spread out in the surrounding air before settling back onto nearby surfaces. At some point between dispersion and resettlement, the concentration of dust may be suitable for dust explosions. This illustrates the danger of disturbing accumulated dust. This is important to understand this mechanism as we consider primary and secondary explosions. An initial dust explosion can disturb accumulated dust and generate a secondary dust cloud that can lead to secondary explosions. Depending on the volume of accumulated dust that is disturbed, this secondary explosion can be more severe than the primary.

So how do we prevent risks of both primary and secondary explosions in an AM environment? Let’s reference back to the dust explosion pentagon and recall that if we remove one corner of the pentagon, a dust explosion will not occur.

Oxygen

Oxygen is often removed locally at the AM process, selective laser sintering for example is often conducted under a forced argon environment. However, for obvious reasons, it is not practical or safe to remove oxygen from the wider manufacturing environment.

Ignition sources

In a well-managed environment, ignition sources most commonly come in the form of a spark, either from mechanical impact possibly during tool use or from machinery, or the discharge of electricity, possibly an electric fault or from the build-up and discharge of static electricity. However, they can come from any sufficient source of heat such as an open flame, from welding or grinding of metals, or from hot surfaces such as poorly maintained and overheated bearings. The probability of a spark from mechanical impact or an electric arc can be reduced through the use of ATEX-rated equipment, tools, and machinery. Earthing all equipment, installations and even personnel through specific PPE can reduce the build-up of static electricity and thus reduce the probability of electric discharge. Equipment must be well maintained to reduce the probability of malfunction leading to hot surfaces or electric faults.

Fuel

In general, the fuel is the powder material that is the input into the AM process. Thus, it is not possible to remove this element entirely. However, some materials are more combustible than others, so, when possible, a less volatile material should be selected. Additionally, regular cleaning and maintenance supported by sufficient air extraction can reduce the available fuel in an environment.

Dispersion

Similarly to fuel, cleaning and maintenance supported by a sufficient air handling and extraction system will remove the fuel from the environment, reducing the risk of dispersion.

Containment

The removal of containment from the pentagon is not practically possible. This would involve running the manufacturing process outdoors. Furthermore, reducing containment by placing the manufacturing process in a large open-plan space would be difficult too, as the whole space would be subject to the same stringent cleaning and maintenance, as well as the same equipment and ways of working protocols suitable for an ATEX environment.

In review, the most practical way of reducing the risk of a dust explosion in an AM environment is to reduce the likelihood of ignition and, in parallel, reduce the build-up of fuel in the environment.

Relevant Standards and Regulations

ISO/ASTM 52931, titled “Additive manufacturing of metals — Environment, health and safety – General principles for use of metallic materials,” addresses fire and explosion risks in AM environments using metallic powder. It mandates avoiding all ignition sources, including static discharge, hot surfaces, open flames, and live circuitry. Measures to limit static discharge include using grounded antistatic equipment, surfaces, floors, garments, and grounding personnel. Controls must prevent powder from escaping the AM system, with air handling systems capturing powder and minimising atmospheric exposure, and workspaces designed for cleanability.

The Health and Safety Authority of Ireland’s “Guide to the Safety, Health and Welfare at Work (General Application) Regulations 2007 Part 8: Explosive Atmospheres at Places of Work” ² requires employers to take technical and organisational measures to prevent explosive atmospheres or avoid ignition, including electrostatic discharges.

Both documents conclude that to reduce dust explosion risks, all ignition sources must be removed, and dust must be contained and minimised to stay below the lower limit of concentration. This is the same conclusion we arrived on after our interrogation of the pentagon.

Risk of Maintenance

Regular maintenance and well-considered work practices are key to mitigating against dust explosions. However, as discussed by my colleague Mr Nick Ashby in his recent insight article “The Perils of Maintenance,” it is often during maintenance, especially unplanned, that many accidents occur. Stepping away from the day-to-day ways of working to conduct maintenance can lead to an increased risk of dust explosions. Dust that may have been hidden from cleaners can be disturbed when equipment is moved, increasing the fuel load in the atmosphere. Furthermore, the use of tools that aren’t designed for an ATEX environment; conventional hammers may produce a spark when struck off a hard surface, however, specialised bronze-headed hammers will not. A more obvious ignition source is introduced if hot works are required. Nonetheless, not conducting maintenance also increases risk. Thus, the perilous task of maintenance must be conducted, but also de-risked through well-considered risk assessments and ways of working that fully consider the unique requirements of an ATEX environment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while AM technology offers numerous benefits, it also presents additional risks such as dust explosions. Adhering to safety standards, conducting regular maintenance, and ensuring fully trained workers are essential to mitigating these risks and balancing innovation and safety in the exciting world of AM.

About The Author

Jason joined Hawkins in April 2024, he has lead fire investigations in domestic, industrial, and commercial environments. Jason is an accomplished Materials Engineer with a strong background in Additive Manufacturing. He graduated with First Class Honours and conducted research on optimising projection stereolithography additive manufacturing, focusing on the relationships between process parameters, material structure, and mechanical properties. Jason has experience supporting production and optimising manufacturing processes, including laser welding, cutting, and marking. His expertise extends to developing (Eckhoff, 1997) additive manufacturing processes for medical implants and instruments, working with materials like PEEK, nylon, and titanium.

Eckhoff, R. K. (1997). Dust explosions in the process industries. Reed Educational and Professional Publishing Ltd.

Occupational Safety & Health Administration. (2014, May 20). OSHA News Release: After explosion, US Department of Labor’s OSHA cites 3-D printing firm for exposing workers to combustible metal powder, electrical hazards [05/20/2014].

Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/osha/osha20140520-2

Italiano

Italiano