Germination failure for farmers can be expensive. It is not just the cost of the seed but the field preparations and operations before and after the crop failure that need to be taken into account should a failure occur. These include:

- seedbed preparation

- pesticide and fertiliser applications

- sowing operations

- resowing operations

- fuel

- machinery rental

- contractor hire

Added to these will be the loss in yield at harvest because later autumn sowings have lower establishment rates and spring-sown crops yield less than autumn-sown crops. Therefore, farmers could justifiably include all these additional costs if they are making an insurance claim.

The variation in establishment of cereal crops ranges nationally from 2 to 100% according to research data gathered between 1977 and 2002 (Blake et al, 2003). On average it is around 67%, but the expected percentage for wheat, for example, should be 85%. The reason for the actual figure being much lower in commercial practice may be because experimental work done to determine germination is usually sited in the better areas of fields and receives greater care and attention than many commercial crops would. I describe below some of the other reasons for poor establishment:

Whether certified or farm-saved[1], it is important to understand the quality of seed. By law, seed must be officially sampled and tested before it can be certified. Sampling and testing are also important for grain intended for farm-saved seed, although it is not compulsory. Seed certification schemes protect farmers and their customers by guaranteeing that all UK certified seed meets prescribed standards for varietal identity and purity, germination and freedom from foreign material. Sampling and testing determine the cleanliness of the seed and the viability, but if not completed close to the sowing date may impact the accuracy of the results. Tests performed by the seed testing laboratory should include:

- germination percentage

- moisture content

- records of inert matter such as chaff and broken seeds

- identification of non-crop seeds and fungal structures present

Seed Storage

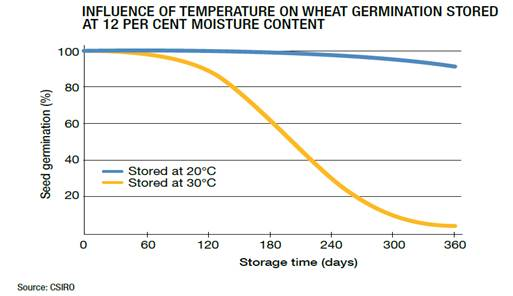

Seed moisture content and storage temperature are critical to maintain quality over the storage period. Generally, wheat seed with a moisture content of 12%, stored at 20°C for a period of 360 days, will retain about 92% germination. However, seed with a moisture content of only three percentage points higher, will result in a mere 27% germination.

Ideally, seed should be stored around 10°C, but the availability of such facilities for bulk storage is limited. The viability of grain deteriorates faster when stored at high temperatures, especially above 20°C. Storage facilities may not be able to keep the temperature below 20°C, especially in the summer months, and with hotter summers as a consequence of climate change, cooled seed storage facilities may become necessary in the future.

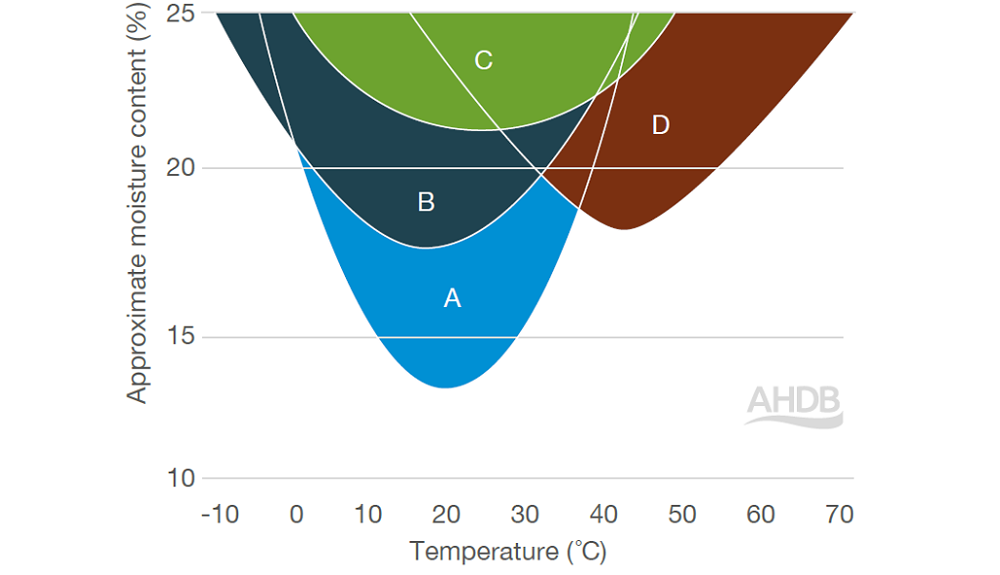

The growth and reproduction of moulds and pests is also influenced by temperature and moisture content. Storage fungi can grow above moisture contents of 14.5% on cereal grain and 7.5–8% oilseed rape seed. The activity of each fungal group depends on a combination of moisture content and temperature. These include the following:

- Aspergillus species which can cause self-heating and damage germination.

- Penicillium species e.g. P. verrucosum, which is active across a wide range of temperatures but when moisture content is at or above 18%, it can produce mycotoxins.

- Advanced decay/field fungi such as Fusarium species, some of which also produce mycotoxins, and heating organisms.

- Thermophilic fungi, which thrive at very high temperatures, such as those that occur in compost bins.

Pests are adapted to the grain storage environment. They can breed at relatively low temperatures and moisture contents. A single insect per kilogram of grain could represent a potentially serious infestation.

Maintaining good hygiene in the store helps reduce insect populations as storage pests can survive on grain residues from the previous harvest and will infest new grain as it is placed into the store.

Common primary species include:

- The grain weevil (Sitophilus granarius) breeds at low temperatures and larvae hollow out the insides of grains, making it difficult to detect. The activity of the last larval stage raises grain temperature locally, causing hotspots. Other pests enter grain that they have damaged.

- The saw-toothed grain beetle (Oryzaephilus surinamensis) feeds on damaged grains rendering them vulnerable to further attack by other pests and by introducing fungal and bacterial infections.

- The rust-red grain beetle (Cryptolestes ferrugineus) prefers higher temperature environments such as those created by the grain weevil activity, but it is one of the most cold-tolerant grain pests and has one of the highest rates of population growth of any grain pest.

Seed Treatment

Seed is usually treated with fungicide or insecticide by specialist contractors after storage and before sowing. Seed should be cleaned to remove impurities such as chaff, weed seeds, soil particles and dust, otherwise the seed treatment will adhere to these instead of the seed.

It is important that the treatment is mixed correctly and applied at the proper rate. Products from well-known agrochemical companies are more expensive, but will be better in the long run because cheaper, inferior products can become lumpy, separate in solution and stick to equipment rather than seed, making them difficult to use.

The products are usually coloured. An even colour all over the seed indicates that the coating has been applied properly, but a patchy appearance indicates it has not and could be a result of poor seed quality, dirty seed, poor product quality or incorrect dilution.

Part 2: Soil and Sowing covers seedbed preparation, sowing operations and environmental conditions. This will be published next month.

[1] When harvested seeds from cereals or oilseed rape are used to establish a subsequent crop, it is called farm-saved seed (FSS). Farm-saved seed differs from officially certified seed, which meets specific conditions and controls for sale – relating to, for example, germination capacity, varietal identity/purity and contaminant levels.

About the Author

James has over 20 years’ experience in his field, and is experienced in investigating the causes of plant diseases, crop failures and spoilage of fresh produce.

He has worked on projects to breed genetic resistance to diseases in oilseed crops and published research into the effects of climate change on plant diseases in the UK. James has also managed a portfolio of field and glasshouse research projects, gaining extensive experience in plant disease diagnostic techniques.

James joined Hawkins after four years at Berry Gardens Growers, the UK’s leading berry and stone fruit cooperative. During his tenure, he set up the plant disease diagnostic laboratory, and used his expertise to diagnose crop problems and fruit rots and advise growers on disease management strategies.

James is a Senior Associate based in our Reigate Office and has investigated cases of crop germination failure, crop storage problems, fallen trees, mould contamination, pesticide damage, wildfires and plant disease outbreaks in domestic and commercial settings.